Introduction: Third Cinemas: Exploring Nomadic Thoughts & Narrative Communities

The sections of this book are arranged in a roughly chronological order and, as such, the structure of this book itself tells a kind of story. It is not simply a story of my own personal and intellectual journey, but rather a narrative in which I have participated, often without knowing where it was leading me. I could not have foreseen the changes that would occur, the trajectory that my work would follow. This book recounts a narrative that I did not plan; it records a journey that I never expected to take.

The journey of this book cannot be charted in linear terms, either temporally or spatially. Its movements do not proceed in a single direction, but meander, crossing back and forth between old and new, myth and science, magic and technology. Indeed, the writing of these essays itself moves and changes over time. The essays collected here tend increasingly to become removed from Western forms of argumentation, less "academic" in their form. They become a series of "Notes" and "Theses," in which various points and anecdotes are collected, juxtaposed, and linked. They wander, sometimes pausing to tell stories or share poetic images. By the standards of academia, they are loose, perhaps even unfocused. They don’t present clear points and then support them, but move off in odd directions. In a sense, they mimic the forms and movements of the films, cultures, and topics that they discuss, from nomads to ruins, from stones to the wind.

One might therefore view this volume as a kind of map, which did not exist prior to the journey. It is only in retrospect that the movements inscribed here can be discovered and traced. It is only in the telling itself that the story makes itself heard. We can see only where we have traveled by looking back.

Looking back is especially important in this age of new technologies, of computers and wireless communication and biotechnologies that often seem to have left the past far behind. Memory is an important link between the vastly different realms of the past and the present. Memory, after all, is never simply a matter of the past, but also of the present. We look back from where we now are. It is also important to recall that memory, which seems so essential to our identity as human beings, is a crucial element of today’s "new" electronic and genetic technologies as well. As this volume moves from ancient myths to cinematic images to modern digital technologies, we must remember the links that connect them.

Without memories, the future is impossible, not because the past can predict what will happen, but because it allows us see the movements and paths that we have unwittingly taken. It is memory that allows our stories to be recorded, to be written. Writing is itself a form of memory, as are visual records. From stone carvings to videodisks, people have always attempted to mark their passing, the movements of which they were a part. Yet, memory is itself always moving, changing one thing into another. We follow those movements. That process is what is recorded, marked, here.

Part I

The initial selections in this section are drawn from my book Third Cinema in the Third World and are intended to introduce students and others to the study of "third cinema." Many of the films and filmmakers that have been described as being part of the "third cinema" were from the so-called "third world." Yet, "third cinema" does not simply mean the films of the "third world."

The term "third world" was originally coined to contrast those countries of Latin and South America, Asia, and Africa with the "first world" of capitalist countries and the "second world" of the Soviet bloc. It was a political term intended to highlight the joint interests of these countries. Yet, the term eventually came to be little more than a synonym for poor or "underdeveloped" countries. Today, "third world" is most often used as a patronizing description of technologies or conditions that are considered unacceptable by the standards of supposedly highly-developed countries. Thus, the term has lost its original, politically-charged meaning.

It was, however, in the charged political climate of the 1960's that the term "third cinema" came to prominence. Argentine filmmakers Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino, for example, used the term to describe films, like their own Hour of the Furnaces, that sought to break from the traditions of Hollywood on the one hand and European art films on the other. There was a clear political impetus to these films, many of which were revolutionary not only in their political sentiments, but also in their formal construction. They exposed the arbitrary rules underlying traditional filmmaking styles in much the same way that they worked to bring repressive social and political structures to the consciousness of their audiences.

In Third Cinema in the Third World, I further elaborated the idea of third cinema, distinguishing between films that were simply made in "third world" countries and those that took up the challenge of a different approach to filmmaking, both in content and in form. There were—and continue to be—many films made in various countries of the so-called third world (a number of countries in fact make more films each year than are made in Hollywood). Yet, the majority of these films were made within studio systems that forced them to become apolitical in content and formulaic in style. Thus, not every film made in the third world can be considered third cinema. By the same token, there are a number of films that, although they were made in "developed" countries, might be considered third cinema films by virtue of their political and formal concerns. Thus, for example, the films of African-American independent filmmakers such as Charles Burnett and Julie Dash and those of the British filmmakers in the Black Audio and Sankofa collectives are considered every bit as much a part of "third cinema." Third cinema is much more an attitude toward filmmaking than a matter of place or of any particular thematic or formal elements. Thus, despite the important differences between third cinema films from Africa, Asia and Latin America, or the Handsworth district of London, they are bound by this shared attitude.

In the following selections, I have highlighted examples of African cinema, which should serve as examples, not only of third cinema, but of the important cultural differences that underlie these films. Often, students viewing African films for the first time may find these films confusing, or even irritating. In part, these reactions are due to a lack of understanding of the cultural practices that are depicted in these films, but also a misunderstanding of how cultural differences shape the form of these films as well. When Ousmane Sembene, for example, shoots a scene from multiple angles around a circle, as in many of his films, ignoring the tradition of the 180 degree rule, he does so not because he has not yet learned how to shoot films "correctly," but because of a different cultural view of space. Thus, in introducing readers to these films, I also hope to further their understanding of the important differences between cultures, cinemas and aesthetic differences.

The later essays in this section continue to deal with the cultural, political and formal differences between "third cinema" and Western films, but at a more general level. These essays are focused less on individual films than on broader theoretical concerns. Theory, however, should be taken here not merely in the sense of an overarching conceptual framework that can then be applied to specific examples. Theory, for me, is inevitably a matter of theorizing, which means that theories are always in the process of change.

Part of what begins to change in these essays is my conception of third cinema. If, in "Towards a Critical Theory of Third World films," I sought to elaborate a schematic overview of third cinema and its relation to other kinds of filmmaking, I also began to change the emphasis of my thinking. I began, in short, to think of third cinema less in terms of typologies and structural oppositions than in terms of various cultural metaphors that suggested more complex, non-binary relations. This shift was, no doubt, a reflection of changes in third cinema itself, but also of more general changes in cultures and cultural theories. Particularly important to this shift in my thinking and writing was the figure of the diaspora, with its connotations of simultaneous movement and connection, its implication of a collective memory and identity that is neither static nor essential, but continually in flux. These notions of diasporic movement, memory, and identity increasingly became part of my conception of third cinema. In a sense, my own critical thinking was becoming increasingly less fixed, and more open to several possibilities to styles and meanings. My writing was itself becoming more diasporic, more dispersed and roaming.

My shift in thinking was aided by several fortunate occurrences. The first was my debate with Julianne Burton in the pages of Screen, for which I wrote "Colonialism and Law and Order Criticism." The second was the 1986 Edinburgh International Film Festival on Third Cinema, which inspired me to write "Third Cinema as Guardian of Popular Memory: Towards a Third Aesthetics." I must thank Julianne Burton for her essay, "Marginal Cinemas and Mainstream Critical Theory," which prompted me to think more seriously about the relationship of theory to practice, particularly in relation to Third Cinema (switching here to upper case). I felt then, and continue to believe, that Burton had mistakenly characterized Third Cinema—and by extension the Third World—using Western modes of thinking as a point of reference. If the West, or Western critical theory, is figured as central, then the practices of Third Cinema will necessarily be seen as peripheral or "marginal." From this perspective, Third Cinema becomes merely the Other of Western cinematic theories and practices, in the same way that women have been represented as the other by which man defines himself. This sort of oppositional thinking is itself a reflection of Western cultural traditions, which seek to maintain a sense of "law and order" by continually distinguishing between center and margins, interior and other. It was precisely as an alternative to these binaristic tendencies that the idea of Third Cinema—and of the Third World itself—came into being.

It was in this context that I began to move toward a "Third Aesthetics" that would not simply be cast in terms of binary oppositions, including those of theory and practice, creation and criticism. In "Third Cinema as Guardian of Popular Memory," I posed popular memory in contrast to notions of "official" history, arguing that Third Cinema becomes an ongoing repository of people’s histories and mythologies. In a sense, Third Cinema takes up the function of the African griot, the oral storyteller who serves as the keeper of the stories and histories by which peoples define themselves. It worth noting that this kind of collective popular memory is capable of allowing people to maintain a sense of identity through all manner of travels and travails, including migration, immigration, and even forced relocation and slavery. Yet, while some might imagine popular memory as the stable, unchanging center around which identity revolves, we must also remember that memory is itself dynamic and fragmentary. Unlike "official" histories, with their pretense of being comprehensive and complete, popular memory is a collection of myths and tales that always remains partial: complexly linked, but incapable of being totalized in a single narrative. Just as diasporic identity is multiple and mixed, so too is popular memory. Yet, as I argued in this essay, storytelling and memory should not be relegated to the "other" side of a divide from theory and criticism. Critics construct fictions just as much as any storyteller, but they rarely acknowledge the constructed nature of their own work. Indeed, looking back now, I can see that this point was an extremely important one in my journey, for my work from this point forward would increasingly intermingle critical theory and storytelling, analysis and memories.

Part II

If the essays in the previous section displayed the growing importance of the idea of the diaspora in my conception of third cinema, the essays in this section may be seen as a further development of these ideas, applied not only to cinema but to aesthetics and culture more generally. These essays revolve around issues of cultural identity. Unlike traditional Western notions of identity, with their emphasis on fixity and boundaries, the notions of identity explored in these essays are more open, more fluid, less defined by boundaries between us and them, interior and exterior, self and other.

Memory continues to play an important role in these issues of identity. In "Theses on Memory and Identity," I drew on elements from my own memory, mixed with theoretical reflections, in order to discuss issues of identity and origin, particularly within diasporic populations. African-descended peoples, for example, often have a strong sense of connection to, and memory of, Africa—even when they have never been there. This is not, however, an argument for some form of African essentialism, or for a literal "return to Africa." As I argued then, the origins of identity always remain, to some degree, inaccessible. Identity arises as much from the search, the journey, as from some idealized final destination.

A similar emphasis on movement and journeying is obvious as well in "Thoughts on Nomadic Aesthetics and the Black Independent Cinema." In this essay, I took up the figure of the nomad as a means of elaborating an aesthetics appropriate to black and diasporic cultures. In contrast to Western notions of idealized, eternal beauty, a "nomadic aesthetics" suggests an aesthetic that is always in process, traveling, perpetually unfinished. The nomad does not travel simply to get to a particular destination; the journey itself becomes the nomad’s life. Nomadic aesthetics is similarly open; it is not defined by a beginning point, nor does it move toward a completed end. Just as nomadic peoples pay little attention to national borders, nomadic aesthetics is based upon crossing boundaries, moving in the spaces between jurisdictions, genres, categories. Indeed, nomadic aesthetics often moves between the physical and spiritual worlds, blending mythic elements with practical and political concerns. Not surprisingly, then, films and other artworks that draw inspiration from the nomadic often appear unsettling, undirected, imperfect, jumbled, for they are never "pure." They move between documentary and fiction, poetry and analysis, folklore and science.

The final essay of this section, "Ruin and the Other," combines many of the elements from my earlier essays into the metaphor of ruins. Ruins preserve our memories, our history, and our identities. Yet memory itself, as I argued then, "is always a ruin—scattered, buried and invisible." Ruins, then, cannot be treated simply as relics frozen in time, nor as fragments of a past that one might restore to wholeness. Such a restoration of a glorious imaginary past was, we should remember, the goal of fascism. If ruins, like memory, are fragmentary, they are also mobile, shifting, capable of being rearranged, reinterpreted, remotivated. Rather than seeing ruins as indicative of a loss, we should see them as a repository of memory. In the same way, we should not base our notions of identity on a restoration of lost wholeness (which is always imaginary). We must instead learn to live among ruins, among our cultural memories, drawing strength from the ephemeral spirits of our past.

It is particularly important to note that in these essays, memory and identity, nomads and ruins, become more than simply a matter of content; they also become models for the essays themselves. That is to say, the writing in these essays begins to mirror the topics that they discuss. In keeping with the more fluid and nomadic notions of identity explored here, the essays themselves, one might say, tend to be more fluid in form, more mixed, more fragmentary, more nomadic. Stories, anecdotes, and poems take on an increasing weight in these essays, mixing with theoretical and analytical points. As in the nomadic view of life, these elements are interconnected, but not always in a rational or analytical manner. In retrospect, I can see that it would have made little sense to write about ruins or nomadic aesthetics without practicing what I was writing about. But I cannot claim that this shift in my style of writing was entirely planned; it was as if the topics themselves called forth this more mixed, ruined, nomadic form.

If the essays of the previous section demonstrate my increasing interest in linking the content of writing with its form, and in the interconnection of seemingly far-flung ideas and elements, the essays in this final section continue this tendency. They are perhaps the most removed from the traditional academic essay, with its emphasis on directed, rational argumentation, on moving toward a clearly-defined end. More evocative than argumentative, these essays may be seen by some as lacking direction, as meandering. They wander from point to point, pausing to tell an anecdote, to cite a quotation, to recall a half-remembered fragment from my own childhood. Images from films intermingle with oral tales, poetry with theoretical speculations, discussions of contemporary technologies with examples of ancient practices.

At times, these essays become intensely contemplative and personal, as in "The Intolerable Gift." Occasioned by my return to my native Ethiopia after a long absence, much of this essay is autobiographical. Indeed, it revolves around two gifts given to me by mother, which inspired me to reconsider my own sense of identity. In these gifts, I found a figure for my life, both as a professor of film studies in Los Angeles and in relation to my African past, my Ethiopian heritage. I called these gifts "intolerable" precisely because they cannot be reduced to the categories of modern and traditional, Western and African. They are intolerable because they create a debt that cannot be measured or repaid, because they cannot be assessed from a critical distance. This is a gift—an always personal gift—that the scientific and critical traditions of the West cannot easily receive, for they invariably exclude it as too personal, too emotional, too irrational, to count as knowledge. As both feminists and non-Western scholars have noted, this kind of binary differentiation has often been the basis on which the West has excluded the discourses of its others. In other words, the West has, for the most part, always refused to accept the intolerable gift—and the responsibilities that it imposes.

The next essay in this section, "Notes on Weavin’ Digital," may seem very far-removed from the concerns of "The Intolerable Gift," since it deals with issues involved in contemporary computer and digital technologies. Yet, this essay approaches these "new" technologies by comparing them to traditional practices of weaving. The metaphor of weaving is, first of all, an important if generally ignored part of digital technologies, as the figure of the Web demonstrates. What is implied by webs and networks is a notion of interweaving: that is, of connection or interconnection. In this sense, the worldviews of traditional weaving cultures and digital cultures coincide: both tend to see everything as connected, interwoven. This sense of connectedness, as we noted in this essay, "extends the boundaries of the individual." One becomes part of a greater pattern, an immense, densely interconnected community. This kind of networked identity and thinking is rhizomatic rather than rooted, parallel rather than serial, a-rational rather than rational (or irrational). Thus, the paradigms involved in weaving offer opportunities for Third World peoples to engage in new technologies, as well as new (or is it ancient) ways to think about global interconnection.

The final short essay of this section, and of this volume, is yet another metaphorical excursion, built this time around the figure of "Stone." Indeed, this essay endeavors to think not simply about "stone," but through "stone." Of course, stones are supposedly mute, but as I argue here, they have their own kind of language—a language that we often fail to recognize. Stone walls and tablets were, after all, the first instruments of writing. Stones must therefore be listened to, not only as monuments of history, but as signs that mark the path to the future. Stones tell powerful stories, and small ones, from the Pyramids to the desert rocks on which Native Americans marked their spirit symbols. Since stones are frequently used as markers of death and of religious memorials, they also imply a connection to the spiritual, to a space beyond the merely material. Perhaps, then, what stones struggle to tell us is precisely the possibility of what cannot be simply or clearly represented in written signs, in material terms.

Indeed, it seems that in each of the essays in this section, I am struggling to represent things that can never be reduced to representations, to words. Perhaps this is why these essays seem to wander, to move in several directions at once, for they seek to escape the constraints of categories and structures, although of course they can never entirely do so. But that is precisely the point: we live among ruins and stones, among imperfect representations. The journey is the destination.

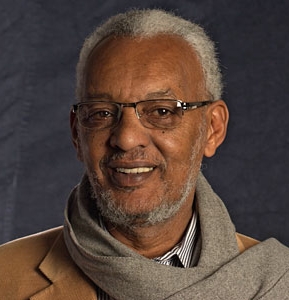

Teshome Gabriel, Ethiopian-born American cinema scholar, longtime professor at the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television, and expert on cinema and film of Africa and the developing world.

Teshome Gabriel, Ethiopian-born American cinema scholar, longtime professor at the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television, and expert on cinema and film of Africa and the developing world.